On 6 August, the Church celebrates the Feast of Christ’s Transfiguration. This edition considers the importance of this mystery and proposes some resources for delving into it.

- Jesus of Nazareth: From the Baptism in the Jordan to the Transfiguration

by Benedict XVI - Light on the Mountain: Greek Patristic and Byzantine Homilies on the Transfiguration of the Lord

by Brian E. Daley SJ - The Uncreated Light: An Iconographiocal Study of the Transfiguration In the Eastern Church

by Solrunn Nes - Light and Glory: The Transfiguration of Christ in Early Franciscan and Dominican Theology

by Aaron Canty - Thomas Tallis, Sacred Choral Works: Spem in alium

The Sixteen, directed by Harry Christophers

The Feast of the Transfiguration was first celebrated toward the end of the fifth century or at the beginning of the sixth. Possibly, the dedication of the basilicas on Mount Thabor, the site of the Transfiguration, prompted the introduction of the feast.

According to tradition, the Transfiguration took place forty days before the Passion. As the Exultation of the Cross was celebrated on 15 September, the Feast of the Transfiguration was set forty days earlier, on 6 August.

Originally, the feast was celebrated in the churches of the East. From the ninth century on, it spread throughout the West. One of its main promoters was Peter the Venerable, abbot of the influential monastery of Cluny, who even wrote an office for the feast.

For many centuries, however, it was celebrated as matter of local custom in the West. It was only in 1457 that it was incorporated into the Roman Calendar. Calixtus III incorporated it in thanksgiving and commemoration of the victory against the Turks at the Siege of Belgrade in 1456. By some accounts, the turning point of the campaign, led by John Hunyadi and St. John of Capistrano, came on 6 August.

The Transfiguration features at other moments of the liturgical year. Just as Jesus prepared Peter, James, and John for his Passion with his radiant Transfiguration on Thabor, so do we contemplate this mystery on the Second Sunday of Lent to prepare us for Holy Week. We thereby follow a practice that goes back to at least the time of Leo the Great.

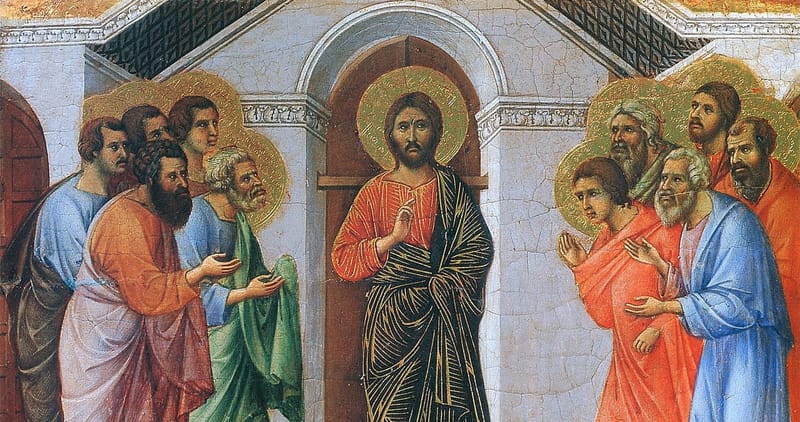

The Transfiguration is one of various moments in which Christ manifests his divinity prior to his Resurrection. He manifested his glory to the Magi, to many others at his Baptism in the Jordan, and to the disciples at Cana. Perhaps more than these other manifestations of Christ’s divinity, the Transfiguration encapsulates and discloses the whole Christian faith.

First, as with Christ’s Baptism in the Jordan, his Transfiguration is a manifestation of the Trinity, the first truth. As St. Thomas Aquinas notes, “The whole Trinity appeared: the Father in the voice; the Son in the man; the Spirit in the shining cloud.” Moreover, the Trinity is manifested through the Son and the Spirit being sent visibly into the world. On the one hand, with his Incarnation, the Son has been sent visibly into the world. At the Transfiguration, the voice of the Father attests to the full identity of Jesus, as does the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the humanity of the Incarnate Word. On the other hand, the Spirit is sent visibly in the form of a cloud.

We perceive God’s invisible nature through visible creatures, as St. Paul reminds us (Romans 1:20). With the sending of the Son and the Spirit in visible, tangible form, the Trinity is revealed to us. Being sent in this way, they reveal themselves and their relation to one another. Only the Son and the Spirit are sent. The Father is not and does not appear in a visible form because he does not proceed from any other. There can be no sending of the Father. The Son is sent first because his eternal procession from the Father is prior ontologically but not in time to that of the Spirit. The Spirit is sent after the Son to indicate that he proceeds from both the Father and the Son.

Second, the radiance that irradiates from the face of Jesus manifests his Incarnation: that he is both true God and true man. Moses’s face was also radiant after he spoke with God. However, he only reflected God’s glory. The light that shines forth from Jesus is that of his own divinity. At the same time, it shines forth from his human body. Not only does it manifest both his divinity and humanity, but also that, through his humanity, God wishes to communicate this light to us and make us “partakers of the divine nature” (2 Peter 1:4). The Transfiguration manifests how God communicates grace to us through the humanity of the Incarnate Word, above all in the sacraments. It discloses the call and path to deification (theosis).

Nevertheless, there is a sombre side to Christ’s conversation with Moses and Elijah. They are talking about his imminent Passion. Then the Christ’s radiant form is overshadowed by the descending cloud. The Transfiguration thereby conveys that, to share in Christ’s glory, we must follow him along the narrow path of the cross.

Christ’s Transfiguration also manifests how all the Scriptures (i.e. the books of the Old Testament) refer to him. Elsewhere in the Gospels, Jesus makes it clear that he is the key to understanding the Scriptures in full. Ultimately, they are about him. He insists that Moses wrote about him (John 5:46). On Easter Sunday, as he accompanies the disciples of Emaus, “beginning with Moses and all the prophets, he interpreted to them in all the scriptures the things concerning himself” (Luke 24:27). Later that day, he opens the minds of the apostles to understand the Scriptures in this same way (Luke 24:44-47). However, this should have already been clear to Peter, James, and John. They had witnessed how Moses and Elijah appeared on Thabor and spoke with Jesus “of his exodus, which he was to accomplish at Jerusalem” (Luke 9:31). Moses represents the Torah; Elijah, the prophets. Through their joint presence at Thabor, they manifest how everything written in the law and the prophets finds it fulfilment in Jesus, along with the indissoluble unity between the divinely inspired writings of the Old Testament and the New. The Transfiguration manifests, therefore, how we should read Scripture.

This is exactly how we listen to Scripture within the liturgy. There, the Old Testament is read each day together with the New, the one in the light of the other, each within the celebration of Christ’s Paschal mystery. By listening to the Word of God in this way in the liturgy, we too partake in Christ’s Transfiguration, just like Peter, James, and John.

The presence of Moses and Elijah is telling in a further way. Each had ascended a mountain to encounter God. Moreover, Moses asked to see God’s glory and face. As this was something no man can do and live, he was only allowed to catch a glimpse of God’s back, after having been shielded in a cleft in the rock (Exodus 33:18-23). Similarly, when God’s glory passed by at Horeb, Elijah covered his face with his mantle as he came out of the cave to speak with the Lord (1 Kings 19:11-13). However, these veiled encounters with God merely anticipated their full encounter with him in the Incarnate Word. Their presence at Thabor indicates that it is in Jesus that we see the face and glory of God.

These are some of the main ways in which Christ’s Transfiguration encapsulates and shows forth the fundamental truths of the Christian faith and life. There is so much more to discover in this great mystery, of course. That is why it is worth looking for some readings that may help us meditate upon it and unpack it in prayer.

You do not need to spend a fortune for a Catholic education.

You need to read the right books

and know how to read them.

1.

Any meditation on the Transfiguration begins with Sacred Scripture’s account of it (Matthew 17:1-8; Mark 9:2-13; Luke 9:28-36; 2 Peter 1:16-18). To unpack these passages from Sacred Scripture, some might wish to avail of modern biblical exegesis. Volume one of Benedict XVI’s Jesus of Nazareth is a good place to start. Not only does it close with a chapter on the Transfiguration but it is also a guide to how we should read Scripture. It attempts to incorporate the valid contributions of modern biblical exegesis while overcoming its limitations.

Of particular interest to Benedict XVI is the typology of the Lord’s Transfiguration and whether the primary type is Moses’s ascent to commune with God in Exodus 24 or the Feast of Tabernacles.

According to some exegetes, Exodus 24 is the primary type. Just as Moses ascends Sinai with Aaron, Nadab, and Abihu, so does Jesus bring Peter, James, and John with him up Thabor. Moreover, just as the cloud descends upon Sinai, so too does the Holy Spirit descend in the form of a cloud upon Jesus. Indeed, Jesus appears as the fulfilment of the tent of meeting.

On the other hand, there are indications that the Transfiguration took place during the Feast of Tabernacles. That would explain Peter’s proposal to raise three tents.

In all likelihood, both readings are equally valid given the way this mystery condenses so many aspects of the divine economy.

Also important for Benedict XVI is the way in which the Transfiguration teaches us of the need to pass through the cross to partake of Christ’s glory.

“We, pilgrims on earth, are granted to rejoice in the company of the transfigured Lord when we immerse ourselves in the things of above through prayer and the celebration of the divine mysteries. But, like the disciples, we too must descend from Tabor into daily life where human events challenge our faith. On the mountain we saw; on the paths of life we are asked tirelessly to proclaim the Gospel which illuminates the steps of believers.”

John Paul II

2.

Another excellent resource for unpacking the spiritual riches of Christ’s Transfiguration, especially since it introduces us to the teaching of the Church Fathers, is Light on the Mountain: Greek Patristic and Byzantine Homilies on the Transfiguration of the Lord by Fr. Brian E. Daley SJ.

In this volume, Fr. Daley introduces and translates twenty-three Greek homilies written between the third and the fourteenth centuries.

The collection begins with a homily by Origen and ends with two by Gregory Palamas. In between, there are homilies by several Church Fathers such as Saints John Chrysostom, Cyril of Alexandria, Andrew of Crete, and John of Damascus. There are even three homilies by a Byzantine emperor, Leo VI, relics of time when princes not only promoted the Christian faith but received a rigorous theological education to do so.

Obviously, Origen's homily was delivered long before the Feast of the Transfiguration ever existed. In fact, only about half of the homilies in the collection were written for the feast. The other half were delivered as part of a series of catecheses or commentaries on the Gospel.

This collection of Greek homilies on the Transfiguration, full of spiritual and doctrinal insights into the mystery, is an excellent resource for prayer and lectio divina.

"On the transfigured face of Jesus a ray of light which he held within shines forth. This same light was to shine on Christ's face on the day of the Resurrection. In this sense, the Transfiguration appears as a foretaste of the Paschal Mystery.”

Benedict XVI

3.

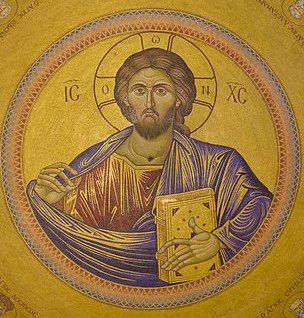

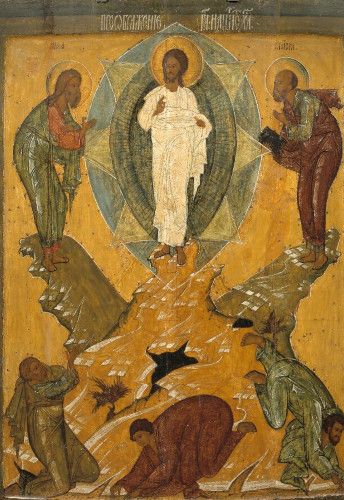

Homilies are an integral part of the liturgy, but so are sacred images. One of the homilies in Daley’s collection brings this out. It was delivered by Athanasius of Sinai, a seventh-century abbot of St. Catherine’s Monastery on Mount Sinai. Some of his reflections probably refer to the monastery’s magnificent mosaic of the Transfiguration (565) that the monks would have viewed while he preached. Art historian and iconographer Solrunn Nes offers a probing artistic and theological analysis of this mosaic in The Uncreated Light: An Iconographiocal Study of the Transfiguration In the Eastern Church.

Among the other representations of the Transfiguration that Nes examines are the central mosaic of Ravenna’s St. Apollinaris in Classe (549) and an Ottonian illuminated manuscript (1021-50, Bamberg State Library Msc. Bibl.94, fol. 155r.). She also surveys three fifteenth-century icons in Russian churches by Theophanes the Greek, Andrei Rublev, and the Novgorod School respectively.

Mirroring the Transfiguration, Nes divides her study into three parts: ascent, vision of light, and descent. First, she considers the formal pictorial language of the works. Second, she considers the theological interpretation of the Transfiguration and offers a defence of hesychasm. Third, she compares the icons considered in the light of the Orthodox spiritual tradition.

While Nes focuses on the Eastern Church’s artistic and spiritual tradition. Unfortunately, there does not seem to be a comparable study of the Transfiguration in Western sacred art. Nevertheless, Nes’s study provides a template for contemplating Western sacred art’s depictions of the mystery.

4.

The last two books attest to centrality of the Transfiguration in the theology and spirituality of the Eastern Churches and are motivated in part by the extensive reflection of modern Orthodox theologians on the mystery. Overall, the Transfiguration figures more prominently in the liturgy, theology, and spirituality of the Eastern Orthodox churches. Not only is 6 August one of their Twelve Great Feasts. Especially since Gregory Palamas on, the mystery of the Tranfiguration has been viewed as a sort of summation of the Orthodox faith.

However, the Western Church’s reflection on this mystery is no less important. An interesting study in this regard is Aaron Canty’s Light and Glory: The Transfiguration of Christ in Early Franciscan and Dominican Theology.

Canty shows that, for the most part, the Transfiguration did not feature among the questions addressed in the medieval summae or commentaries on Peter Lombard’s Sentences. That changed for a brief period, between roughly 1230 and 1280, when early Franciscan and Dominican theologians made the Transfiguration the object of their academic research and teaching.

They were intrigued by the various questions that the Transfiguration raised. What do the Gospels mean when they report that Christ was transfigured? How is his hypostatic union the source of the light he radiates? How and why did he radiate this glory prior to his glorification but chose not to do so after his Resurrection?

In their preaching and exegetical works, the same theologians tend to focus more on the spiritual import of the Transfiguration.

It is St. Thomas Aquinas, however, who building on their work and through his deep study of the Church Fathers, provides the most comprehensive treatment of the mystery, one which is both speculative and spiritual.

Moreover, St. Thomas is the only member of this group to stresses the same point as Benedict XVI’s Jesus of Nazareth. Canty points out that, “Of all the theologians from the period, only Thomas repeatedly reminds his readers that the glory signified by the transfiguration is attained by following Christ in His passion and death.”

However, as Canty also notes, scholastic theologians working after St. Thomas showed little interest in the Transfiguration but returned largely to the set of questions on Christ that twelfth-century theologians had considered.

5.

Just as homilies and sacred art are integral parts of the liturgy, so too is sacred music. This survey or resources for meditating on the Transfiguration should close, therefore, by selecting some sacred music written for the Feast of the Transfiguration.

The mystery has even been the subject of a major work of twentieth-century classical music: Olivier Messiaen’s La Transfiguration de Notre Seigneur Jésus-Christ. However, while the great French composer’s tribute expresses his deep faith and piety, it is probably too challenging a work and way-out-there for the uninitiated. Moreover, it was written for the concert hall, not the cathedral.

A far more accessible and liturgically suitable work is Thomas Tallis’s setting of part of the the Latin hymn O nata lux, published in his and William Byrd’s 1575 collection, Cantiones Sacrae.

O nata lux is a liturgical text. Formerly, it was the hymn recited at Lauds on the Feast of the Transfiguration. Currently, it is the hymn for the First and Second Vespers for the feast.

Tallis and Byrd were Catholics who worked mainly for Anglican patrons. The Latin motets of their Cantiones Sacrae collection attests to the Catholic faith. At the same time, the homophonic style of O nata lux is more redolent of Anglican hymns of the period and the Reformation’s preference for musical settings that preserved the intelligibility of the text. It concludes with a dissonance, that may be meant the way in which Christ’s Transfiguration points forward to his Passion.

A beautiful yet accessible contemporary setting of O nata lux has been written by the American composer Morten Lauridsen.