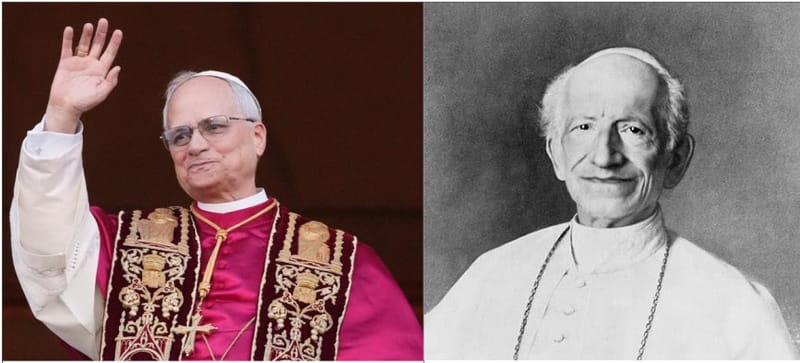

Earlier this week, Card. Robert Francis Prevost was elected to the See of Peter. He took his name from Leo XIII, inspired by that pope’s seminal encyclical, Rerum novarum. He has thereby invited the Church to study and apply anew the social doctrine of Leo XIII. To commemorate the election of Leo XIV, this edition of Five Books for Catholics proposes some resources for reading the social doctrine of Leo XIII in all its breadth.

- The Great Encyclicals: Volume One, The Social Letters

by Leo XIII, compiled and with an introduction by Leo L. Clarke - The Great Encyclicals: Volume Two, The Spiritual Letters

by Leo XIII, compiled and with an introduction by Leo L. Clarke - The Church Speaks to the Modern World: The Social Teachings of Leo XIII

edited by Étienne Gilson - Catholic Social Teaching: A Volume of Scholarly Essays

edited by Gerard V. Bradley and E. Christian Brugger - On the Dignity of Society: Catholic Social Teaching and Natural Law

by F. Russell Hittinger, edited by Scott Roninger

What’s in a name? Quite a lot when it is a pope’s. During the last century, the Bishops of Rome have made a statement of intent with their chosen name.

John Paul I and II took the names of the two popes who had presided over Vatican II. They thereby signalled their commitment to put the council into practice.

Joseph Ratzinger sought to emulate Benedict XV, “a true and courageous prophet of peace,” while evoking St. Benedict, the patriarch of Western monasticism, and “a fundamental point of reference for the unity of Europe and a powerful call to the irrefutable Christian roots of European culture and civilization.”

Jorge Mario Bergoglio picked St. Francis on account of his love for all persons, the poor, and creation. He thereby broke with the custom, which goes back to the eleventh century, of choosing not only the name of an earlier pope as a sign of continuity but also the name of a pope from the first millennium.

Robert Francis Prevost, on the other hand, has gone back to that tradition. As he has explained in his inaugural address to the College of Cardinals, his chosen name expresses his intention to continue Leo XIII’s response to the social question.

“I chose to take the name Leo. There are different reasons for this, but mainly because Pope Leo XIII in his historic Encyclical Rerum Novarum addressed the social question in the context of the first great industrial revolution. In our own day, the Church offers to everyone the treasury of her social teaching in response to another industrial revolution and to developments in the field of artificial intelligence that pose new challenges for the defence of human dignity, justice and labour.”

Leo XIV singled out his predecessor’s Rerum novarum. Some might assume, therefore, that Leo XIII’s social doctrine is contained entirely in that encyclical. It is not. At least, that is not how Leo XIII saw things.

In an apostolic letter written toward the end of his pontificate, Vigesimo quinto anno, Leo XIII outlined the pastoral strategy he had pursued. His goal was to Christianize the family and society. To that end, he focussed on spreading the treasures of the Church’s teachings. Significantly, he lists as the chief acts of his pontificate the encyclicals on:

- Christian philosophy (Aeterni Patris);

- human freedom (Libertas praestantissimum);

- marriage (Arcanum);

- freemasonry (Humanum genus);

- the origin of civil power (Diuturnum);

- the Christian constitution of states (Immortale Dei);

- socialism (Quod apostolici muneris);

- the condition of workers (Rerum novarum);

- and the principal duties of Christians as citizens (Sapientiae christianae).

This list is important for several reasons.

First, by referring to these encyclicals as the chief acts of his papacy, Leo highlights that his main contribution was his systematic exposition of Christian doctrine amid radical social changes. In this regard, Leo developed the template that his successors have followed.

The French Revolution marked the end of Christendom and ushered in a secularist social order. Not only did citizenship replace baptism as the basis of society. The increasingly secularised laws and social institutions were no longer at the service of the Church and Christian life. Now they inculcated a naturalist worldview instead. With the collapse of Christian polities, where the faith was transmitted through the whole fabric of society, the Church would have to rely exclusively on itself to form the faithful. It would have to find new ways to teach the faith both explicitly and systematically. Hence, Leo shifted the emphasis of his papacy away from that of legislator to that of teacher. Whereas Pius IX had condemned the errors of modernity in the Syllabus, Leo focussed on a positive explanation of the faith and its social implications. The encyclical was the medium he developed and perfected. By and large, his successors have followed suit but simply built upon his impressive doctrinal corpus (though not always with his admirable concision).

Second, Vigesimo quinto anno indicates that Leo saw Rerum novarum as just one of his major social encyclicals. Notably, Leo did not speak of ‘social doctrine.’ He spoke instead of ‘Christian philosophy,’ ‘the philosophy of the Gospel,’ ‘Christian wisdom,’ or simply ‘Catholic doctrine.’ However, Pius XI followed up on Rerum novarum with the encyclical Quadrigesimo anno (1931). He noted that Rerum novarum set out “a doctrine on social and economic matters.” As a result, the papal teachings on the modern economy began to be called ‘social doctrine.’ Hence, the magisterial study on papal social doctrine that the Jesuits Jean Yves Calvez and Jacques Perrin published in the late fifties was entitled The Church and Economic Society (that was lost in the title of the English translation, The Church and Social Justice). Rerum novarum constitutes Leo’s social doctrine in this sense of the term. Since Vatican II, however, social doctrine has been construed more broadly and accurately as the Catholic teaching on all facets of society. To find Leo’s social doctrine, in this broader sense of the term, one must look beyond Rerum novarum and delve into his other eight major ‘social’ encyclicals.

Third, Leo does not list his major social encyclicals in chronological order. Ostensibly, he lists them in analytical order. He opens the list with Aeterni Patris, thereby indicating that Catholic social doctrine is not fideistic but rational and founded on natural law. This is the basis for the Church’s dialogue with secular society. Furthermore, by mandating the study of St. Thomas Aquinas, he also indicated that the Angelic Doctor provided the doctrinal framework of his own social encyclicals. In fact, Leo advocated Christian philosophy, scholasticism, and St. Thomas primarily as a means to addressing the social issues of the day. Aeterni Patris is not just one of Leo’s major social encyclicals but in some ways the foundational one.

Next on the list is Libertas praestantissimum. It counters the underlying anthropology of liberalism by unpacking the Christian conception of freedom and obligation.

It is followed by Arcanum. This great encyclical figures precisely because marriage is the fundamental human society. Indeed, as Russell Hittinger has pointed out in various articles, Catholic social teaching is largely about the proper relationship between the three necessary societies of marriage, polity, and Church. Arcanum is also one of the most fundamental of Leo’s great social encyclicals.

The social character of the other six and the analytical order between them are more apparent.

1. & 2.

In Vigesimo quinto anno, Leo tells us what his major encyclicals are. Curiously, Leo L. Clarke, does not follow Leo’s indications in his recently published collection of the pope’s great encyclicals.

Clarke divides his edition into two volumes: the first, a collection of “the social letters”, the second of “the spiritual letters.”

In the latter category, Clarke places those letters that "more explicitly and extensively address the theology and practice of the Catholic religion—our love of God and His love for us—while the ‘social encyclicals’ included in the companion volume address more the philosophical and normative principles that govern the lives of Catholics in society.”

Clarke acknowledges that his manner of distinguishing between social and spiritual encyclicals “is necessarily a matter of discretion because Pope Leo's teachings on faith and morals permeate all his writings.” However, whereas Leo XIII clearly takes Aeterni Patris and Arcanum to be fundamental social encyclicals, Clarke includes them in the second rather than the first volume. This is particularly unhelpful since Leo’s encyclical on marriage underlies Rerum novarum’s teaching on property, subsidiarity, and the right to form associations. Catholic social teaching is largely about marriage and family.

For this reason, Russell Hittinger recommended Leo’s Arcanum along with Pius XI’s Casti connubii as the first encyclicals one should read on Catholic social teaching.

“I tell my students that they should read them first because they lay out the essentials of social ends and forms better than anywhere else. Moreover, they are quite readable. If you read those two and understand them, you will learn eighty percent of what you need to know about CST.”

To its credit, though, Clarke’s collection presents an ample selection of Leo’s encyclicals. The first volume, for example, also features Leo’s letters on “Americanism.” The second volume includes Leo’s two most important doctrinal encyclicals: Providentissimus Deus on Sacred Scripture and Divinum illud munus on the Holy Spirit. It also includes a selection of his encyclicals on the Rosary. These, along with Annum Sacrum, evince Leo’s conviction that lasting social reform can only be brought about through the grace of Christ and prayer. Annum Sacrum, on the consecration of the world to the Sacred Heart, is also notable for its teaching on the kingship of Christ. Pius XI developed that teaching when he introduced the Feast of Christ the King in 1925.

3.

Unlike Clarke, Étienne Gilson’s recently reissued collection of Leo’s social encyclicals follows the selection the pope himself made in Vigesimo quinto anno. The encyclicals are accompanied by Gilson’s excellent introductions and notes.

Gilson’s collection is the one to start with. Clarke’s, with its broader selection of Leo’s doctrinal letters, supplements it.

4.& 5.

Reading Leo’s encyclicals is the best way to study his social doctrine in all its breadth. However, scholarly studies are also a great help at understanding the substance and the context of the arguments he is making.

Two very helpful books in this regard are Catholic Social Teaching: A Volume of Scholarly Essays by Gerard V. Bradley and E. Christian Brugger and On the Dignity of Society: Catholic Social Teaching and Natural Law, a collection of essays by F. Russell Hittinger.

Leo’s social teaching is addressed at various points throughout the first of these two books, but primarily in Chapters Two and Three. The latter is Joseph Boyle’s careful analysis of Rerum Novarum. The former is Thomas C. Behr’s overview of the nineteenth-century context, both intellectual and historical, of Catholic social doctrine. Behr not only gives a brief overview of Leo’s social encyclicals but also unpacks the broader milieu from which they emerged.

Russell Hittinger does this more extensively in “The Accomplishments of Leo XIII,” Chapter Five of his collection.

Both books are worth reading in their entirety because they examine the subsequent development of Catholic social teaching. We cannot read Leo’s social encyclicals and ignore the subsequent magisterium. However, the inverse is also true. The teachings of later popes do not abrogate Leo’s social magisterium but can only be properly understood through it.

Russell Hittinger stressed the importance of Leo’s social doctrine in an interview for Five Books for Catholics. Asked whether Leo’s synthesis is still as pertinent, given Catholic social teaching’s current focus on international affairs and modern social science, he replied:

“My career in writing over the past twenty-five years tells me that it is. In fact, the Leonine synthesis on social order is indispensable.”

Judging by his choice of name, Leo XIV concurs.