Music is an essential part of Christmas. Christ’s birth inspired the angels to praise God with the Gloria (Luke 2:14). Presumably, the angels sang it, like other hymns of praise of praise in the heavenly liturgy (Revelation 5:9). Since then the celebration of Christ’s birth has continued to inspire song throughout the world. It has also been a major source of inspiration for classical composers. Here are five recommended recordings of twentieth-century classical music for Christmas.

- Fantasia on Christmas Carols

by Ralph Vaugh Williams - Lauda per la Natività del Signore

by Otterino Resphighi - Quatre Motets pour le temps de Noël

by François Poulenc - Retablo de Navidad

by Joaquín Rodrigo - Having beheld a strange Nativity (Canticles and Prayers II)

by Georgy Sviridov

For the reasons already mentioned, there is a large body of classical music for Christmas. The library of recordings of that music is even larger. There is plenty to choose from when putting together a list of five recommended classical music records for Christmas.

However, without any further criterion for selecting the entries, the list will be haphazard or simply privilege the more famous pieces. Such lists are ten-a-penny.

Focussing on twentieth-century classical music narrows the repertoire significantly. There is also a pedagogical motive for focussing on it. It is a good way of introducing the uninitiated to some of the more accessible twentieth-century classical music.

During the twentieth century, classical composers experimented with new musical forms and grammar, just as Haydn’s generation moved away from the baroque style, and the Romantics often worked outside the formal constraints of the classical period. However, as in literature and the visual arts, many twentieth-century composers followed the prevalent cultural trend to make a more radical break with the past. Often, they moved away from tonality and everyday song, the basis of traditional musical grammar. Much of the resulting repertoire is challenging. The works that are poorer in quality are often downright unpleasant.

Nevertheless, those unfamiliar with modern classical music should not be put off. Many of the great twentieth-century composers, such as Rachmaninov, Prokofiev, Shostakovich, and Britten, do not abandon tonality at all. Nor do many of the more experimental composers, even though they use it more flexibly. Similarly, while they are breaking with tradition in some regards, they retrieve it in others. They often look back to pre-romantic compositional styles.

Consequently, there is plenty of wonderful twentieth-century classical music that is also very accessible. This includes music for Christmas. Listening to some of these Christmas compositions can help us enter the mysteries and festivities we celebrate. It can also help us discover more twentieth-century classical music.

Moreover, in a Catholic spirit, each of the pieces selected represents a different country and its tradition of Christmas music.

"Ralph Vaughan Williams also played an important role in conserving and spreading the English-language repertoire of hymns and Christmas carols."

1.

Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958) is not only one of the major British composers of the twentieth-century. He also played an important role in conserving and spreading the English-language repertoire of hymns and Christmas carols. The self-described “cheerful agnostic” was the musical editor of two influential collections of English sacred music: The English Hymnal (1906) and The Oxford Book of Carols (1928).

What made him particularly suited to the task was not just his skill as a composer but his credentials as an ethnomusicologist. Like many Eastern European composers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, such as Bartók and Kodály, Vaughan Williams toured the country to collect local folk music and subsequently integrated melodies and motifs from it into his own compositions.

His ethnomusicological work was particularly important for conserving and spreading traditional Christmas Carols. The English-language tradition of Carols originated in the fifteenth century. They were popular songs that, though religious, were a light-hearted and less severe alternative to Latin plainsong. Christmas Carols were a subgenre. Several collections of English Carols were published in the early nineteenth century. The editors of some such collections bemoaned that, even then, the tradition of singing them was dying out and often conserved only in the remoter parts of the country.

Besides the carols that he arranged or composed for The Oxford Book of Carols, Vaughan Williams composed several works for Christmas that draw on the traditional English Carols. The most ambitious of these is his Christmas cantata Hodie (1952). However, his Fantasia on Christmas Carols (1912) for baritone, mixed chorus, and orchestra not only sticks closer to the spirit and style of the source material. Arguably, it is more devout and recollected: better suited to the Cathedral than the concert hall.

As the title indicates, the work riffs on several carols and reworks them into a new and original whole. Like Gustav Holst’s Christmas Day (1910), it reworks four carols: "The truth sent from above"; "Come all you worthy gentlemen"; "On Christmas night all Christians sing" (The Sussex Carol); and “There is a fountain.” The work is written mainly in the Phrygian mode.

Richard Hickox was the first to record the piece, provides an affecting performance, and couples it with some of Vaughn Williams's other Christmas music.

"By using a wind ensemble for the accompaniment, Respighi also evokes the zampogna, the bagpipes of central and southern Italy that are commonly associated with Christmas."

2.

Ottorino Respighi (1879-1936), best known for his orchestral suite The Birds and his tone poem The Pines of Rome, composed a cantata for soloists, choir, winds, and four-hand piano: Lauda per la Natività del Signore (1930). The cantata is a musical setting of the Canticle for the Nativity. Like the Stabat Mater, this poem is attributed, to the Franciscan Jacopone da Todi (1230-1308). The soprano, mezzo-soprano, and tenor soloists represent the angel, Mary, and the shepherd respectively. Respighi even toyed with the idea of setting it for the stage.

Along with some other Italian composers of his generation—such as Ildebrando Pizzetti, Alfredo Casella, and Gian Francesco Malpiero—Respighi strained against the country’s dominant musical tradition, that of nineteenth-century opera. This, along with the similarities in their general approach, led to their being dubbed la generazione dell’Ottanta (the eighties generation).

They drew on the developments in other countries. Respighi, for example, took lessons from Rimsky Korsakov in Russia. They took a greater interest in instrumental music, both orchestral and chamber. At the same time, they were deeply rooted in the Italian tradition. However, they took their cue not from Bellini, Donizetti, and Verdi but from earlier Italian composers, such as Cimarosa, Scarlatti, Vivaldi, and Monteverdi. Respighi, moreover, took a deep interest in Gregorian Chant.

These stylistic traits shine through in Respighi’s Lauda per la Natività del Signore. The text selected evokes the thirteenth-century Italy of St. Francis, whereas, with the use of modes and fragments of Gregorian Chant, Respighi pairs the text with evocations of the musical idiom of the period. By using a wind ensemble for the accompaniment he also evokes the zampogna, the bagpipes of central and southern Italy that are commonly associated with Christmas.

There are few recordings of the work and even fewer available for first-hand purchase. Richard Hickox’s fine recording with Janet Baker may not be easily available. Another option is Anders Eby’s. It too boasts a fine ensemble of singers and pairs Respighi’s Christmas cantata with Saint-Saëns's beautiful Oratorio de Noël.

In the motets, Poulenc combines his gift for unostentatious melody with daring chromatic shifts.

3.

Next stop, France and the Quatre Motets pour le temps de Noël (1952) by François Poulenc (1899-1963).

Like Respighi, music critics discerned that Poulenc and some of his Francophone peers were not following the dominant trends in composition but gestating a distinctive style. They followed in the suit neither of Wagnerian Romanticism nor the ‘Impressionism’ of Debussy and Ravel. Instead, there was a neo-classical inflection to their style, and they had an affinity for popular music, such as jazz, everyday life, and the frivolous. Beyond that, each one’s musical style, influences, and intentions were distinct. Though friends, they did not share a common agenda. In 1920, however, Henri Collet compared them to nineteenth-century Russian nationalist composers, The Five, and nicknamed them Les Six. Alongside Poulenc were Georges Auric, Louis Durey, Arthur Honegger, Darius Milhaud, and Germaine Tailleferre.

In 1936, Poulenc was moved by the death of a young composer, Pierre-Octave Ferroud, in a car accident. He retreated to Rocamadour, a site of Marian pilgrimage that his father held dear. His visit to the sanctuary of the Black Virgin and the simple faith of the pilgrims helped him recover the faith he had abandoned years earlier amid the hedonism of post-war Paris. It also inspired his Litanies à la Vierge noire, a turning point in his output. He began to compose a substantial body of sacred music or, in the case of his acclaimed operatic setting of Georges Bernanos’ Dialogues of the Carmelites, works about the faith. The themes of his non-sacred music also became more substantial.

Emblematic of Poulenc’s later musical and personal trajectory are the Quatre motets pour le temps de penitence for choir (1938-39), three of which are musical settings of Holy Week responsories. They express the sincere faith that he had recently recovered. Maybe, they also express his guilt over his ongoing homosexual relationships.

A companion piece are his Quatre Motets pour le temps de Noël for choir (1952). In each of these motets, the choir sings a Latin text from the Christmas liturgy (1. O magnum mysterium [How great a mystery]; 2) Quem vidistis pastores dicite [Shepherds, tell us whom you saw]; 3) Videntes stellam Magi gavisi sunt [Upon seeing the star, the magi rejoiced]; 4) Hodie Christus natus est [Today, Christ is born]).

In the motets, Poulenc combines his gift for unostentatious melody with daring chromatic shifts. They open by conjuring up the mysteriousness of the Incarnation and culminate in the joyous song in celebration of the Saviour’s birth. In between, they explore the simple faith of the shepherds and the searching faith of the magi.

A good recording of this widely recorded piece is that of The Sixteen, under its founder, Harry Christophers. Sacred music is at the heart of this acclaimed choir’s repertoire. This disk includes not only a fine recording of Poulenc’s Christmas motets but also the other works of sacred music already mentioned and his Mass in G.

"The songs evoke the traditional Spanish repertoire of Christmas Carols or villancicos, and its roots in local folk music."

4.

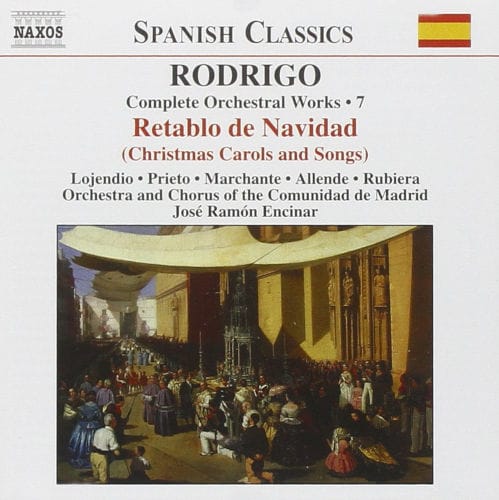

Spain’s tradition of Christmas carols stands out from that of other European nations. It too comprises meditative chants. However, its cheerier ones are particularly lively than rambunctious. Take for example, Aire y donaire from Retablo de Navidad (1952) a Christmas cantata for soprano, baritone, chorus, and orchestra composed by Joaquín Rodrigo (1901-1999).

Rodrigo is one of the major Spanish composers of the twentieth century and is best known for his Concierto de Aranjuez for guitar and orchestra (1939). This work’s haunting second movement was inspired in part by Rodrigo’s grief at the miscarriage of his first child.

The Retablo de Navidad consists of eight songs. Two of the texts are anonymous (Aire y donaire, A la chiribirivuela) and two by the great Spanish poet and playwright Lope de Vega (Pastorcito santo, A la clavelina). The others are by Rodrigo’s wife, Victoria Kamhi.

The songs evoke the traditional Spanish repertoire of Christmas Carols or villancicos, and its roots in local folk music. Rodrigo’s own neoclassical compositional style lends itself well to the task.

While singers such as Victoria de los Ángeles and Plácido Domingo have recorded individual carols from the set, there are only a couple of recordings of the whole work, such as that of the Naxos label.

"The closing hymn discloses the overarching theme of this collection: Christ enters the world so that we might rise heavenwards. He has humbled himself to divinize us."

5.

The pieces selected so far belong to the Catholic tradition of Western Europe. However, it would be unfair to leave out Eastern Christianity’s tradition of sacred music. In this regard, the music of Georgy Sviridov (1915-1998) is particularly. appropriate.

Shostakovich taught Sviridov at the Leningrad Conservatory and considered him one of his finest pupils. Sviridov’s relatively conservative compositional style and his interest in celebrating Russian history and tradition in his music ingratiated him with the Soviet authorities. However, he was a Russian nationalist rather than a party lackey. On the one hand, he did not bow to the pressure to condemn Shostakovich when his former teacher’s Testimony was published in the West. On the other hand, he always considered Orthodoxy to be the wellspring of Russian culture.

Though an accomplished composer of instrumental music, Sviridov excelled as a writer of vocal and choral music. In 1969, he began composing sacred music. His last completed work, Canticles and Prayers for mixed choir. It is a setting of liturgical poetry from the Obikhod. This work is deeply rooted in Russian Orthodoxy’s liturgical charts.

Though a collection of choral settings of liturgical texts, Canticles and Prayers was not intended as a piece of liturgical music. Despite its Christian content, it was conceived as a non-liturgical oratory or cycle, and Sviridov’s original intention, later abandoned, was to write a sort of Mass.

The second of the work’s five parts is entitled Having beheld a strange Nativity (Strannoye Rozhdestvo videvshe) and consists of seven canticles. The fourth and sixth of the canticles are penitential prayers, while the first, third, and fifth are doxologies and recall the acclamation of the angelic chorus at Christ’s birth. The closing hymn discloses the overarching theme of this collection: Christ enters the world so that we might rise heavenwards. He has humbled himself to divinize us.

These recordings can be a gateway into the work of these twentieth-century classical composers. Above all, may they help us enter more deeply into the mystery of the Incarnate Word.