Holy Week should be, insofar as possible, a time of recollection and prayer. To this end, reading one or other of the following books may be useful. It may help us enter more deeply into the mysteries we are celebrating and contemplating. For further recommendations, you can also check out last year’s list.

- Commentary on Saint John the Apostle and Evangelist: Homilies 48-88

by St. John Chrysostom - What is Redemption?

by Philippe de la Trinité - Jesus and the Jewish Roots of the Eucharist: Unlocking the Secrets of the Last Supper

by Brant Pitre - The Crucifixion in Irish Art

by Peter Harbison - Thomas Tallis: The Complete English Anthems

by The Tallis Scholars, directed by Peter Phillips

1.

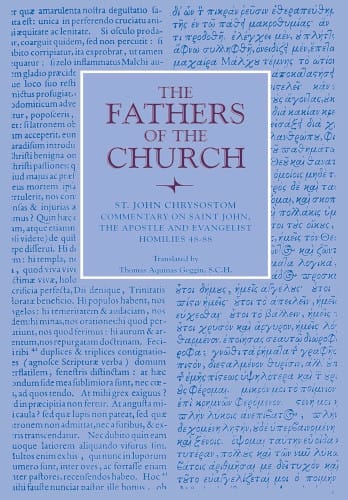

The first recommended book for Lent was by a Father of the Church. This was because we should look to the Fathers, the distinguished witnesses to the apostolic tradition. Moreover, in their preaching they often convey the original meaning of liturgical feasts and seasons. Consequently, their preaching on the Passion of Christ can be especially illuminating when it comes to the mysteries of Holy Week.

This year’s patristic reading for Lent was St. John Chrysostom’s homilies On Repentance and Almsgiving. This Father and Doctor of the Church can also guide us through Holy Week with his Homilies on the Gospel of John.

He delivered them as a presbyter in his native Antioch around 390. Not only was he a native of Antioch. His preaching also reflects that ancient church’s approach to biblical exegesis.

According to some scholars, early Antiochene Christianity stressed the literal sense of Scripture whereas the Alexandrians focussed more on the spiritual sense. Certainly, St. John’s preaching is often direct and to the point. Moreover, he takes every opportunity to underline the practical implications of the Gospel for one’s own life. Nevertheless, he too is attuned to the spiritual sense of Scripture and draws it out opportunely.

In his Homilies on John, Chrysostom explains the significance of the crucified Lord’s pierced side and anticipates a later work of his that is recited during the Office of Readings on Good Friday (Baptismal Catechesis 3, 13-19).

“An ineffable mystery was also accomplished, for 'There came out blood and water.' It was not accidental or by chance that these streams came forth, but because the Church has been established from both of these. Her members know this, since they have come to birth by water and are nourished by Flesh and Blood. The Mysteries have their source from there, so that when you approach the awesome chalice you may come as if you were about to drink from His very side."

Homilies 66-72 cover the events from Palm Sunday up to Holy Thursday, including Christ’s Farewell Discourse, whereas Homilies 83-85 cover the Passion.

2.

The preaching of St. John Chrysostom is often characterised as more catechetical, practical and less speculative that than of other Greek Fathers of the period. Nevertheless, as some have noted, his Homilies on John are more polemical than his sermons on the other books of the New Testament. In them, he often inveighs against Arians and Anomoeans. These two heretical groups had arisen in the fourth century and become widespread. They denied the consubstantiality of the Son and the Spirit with the Father. St. Chrysostom takes advantage of every opportunity the Gospel provides to address their doctrinal errors and misreading of Scripture. This is a salutary reminder that the Trinity and its works are at the centre of all Christian preaching and worship, particularly in Holy Week.

During the Sacred Triduum, we celebrate Christ’s Passion, Death, and Resurrection. However, these are not just events in the life of Jesus. They are works of the Trinity. The creation of Christ’s human nature is a joint action of the three divine persons. The Father has sent the Son into the world and Mary conceives the Incarnate Word by the Holy Spirit, whereas Jesus offers himself up to the Father for our salvation and to merit for us the gift of the Holy Spirit. Moreover, as we meditate upon these mysteries during Holy Week, we try to make sense of Scripture’s various descriptions of Christ Passion, death, and descent into hell. Some of its statements may sound strange to us and leave us not sure what to think. What did Jesus mean as he hung upon the cross and cried, “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?” (Matthew 27:46). How could the Father make the crucified Jesus to be sin (2 Corinthians 5:21)?

These are questions that we might raise in prayer with Christ, especially during Holy Week, when we contemplate the Paschal mystery and hope to grasp its significance. We can find authoritative and reliable answers to these questions in the Catechism of the Catholic Church. Nevertheless, we might still feel that we have not understood them sufficiently. The Carmelite Philippe de la Trinité’s recently reissued What is Redemption? is a clear, penetrating explanation of some of these questions.

The book aims to correct a common misconception of Christ’s Passion. This "doctrinal distortion of the Redemption" and "radical error" is that Jesus “suffered on the cross in order to satisfy retributive justice.’ This misconception has crept in since the Reformation. The opening chapter sets out the evidence of how it has filtered into the Catholic imagination. It arrays a series of texts, mainly from French Post-Reformation Catholic spiritual writers, that describe Christ’s death on the cross as penal substitution, meant to satisfy the Father’s wrath. Some even claim that Jesus suffered the torments of hell. However, Fr. Philippe de la Trinité insists, “the Father did not exercise punitive justice on the Son. He was not, therefore, angry with him, and the Son himself had no sense of his own damnation.”

The rest of the book sets out the more authentic doctrine of our Redemption. It examines the biblical teachings, mainly under the guidance of St. Thomas Aquinas. The central contention is that Christ, the Incarnate Word, redeems us through his vicarious satisfaction and the merits of his charity. By elucidating how Christ has brought about our Redemption, this book allows us to better understand the Paschal mystery.

"In the intense spiritual climate of Holy Week, I invite each of you to contemplate the mystery of the Lord’s Passion, Death and Resurrection in order to draw from it the strength to put the Gospel’s demands into practice in our lives." Pope Francis, 5 April 2023.

3.

On Holy Thursday, Jesus institutes the Eucharist. He does so by eating the Passover Seder with his disciples and telling them to celebrate it in a new way, in remembrance of him. He transforms it by linking it to his death of the cross. The Eucharist is just as much a constituent of the Paschal Mystery as Christ’s Passion, death, and resurrection.

For this reason, one of last year’s recommended books for Holy Week was Scott Hahn’s The Fourth Cup: Unveiling the Mystery of the Last Supper and the Cross. Another informative explanation of the biblical teaching on the Eucharist is Brant Pitre’s Jesus and the Jewish Roots of the Eucharist: Unlocking the Secrets of the Last Supper. It is an abridgement of his more scholarly book on the subject: Jesus and the Last Supper.

In the introduction, Pitre declares that:

“My goal is to explain how a first-century Jew like Jesus, Paul, or any of the apostles, could go from believing that drinking any blood—much less human blood—was an abomination before God, to believing that drinking the blood of Jesus was actually necessary for Christians.”

To resolve this conundrum, not only does he carefully elucidates the Old Testament events and institutions that Jesus brings to fulfilment in the Eucharist, such as the Exodus, the Passover, the Manna, and the Bread of the Presence. He also looks to the extra-biblical sources on Second Temple Judaism and considers how Jesus’s Jewish contemporaries would have understood these Old Testament events and expected the Messiah to bring them to fulfilment. He clarifies Christ’s institution of the Eucharist by setting it within the milieu of Second Temple Judaism.

Moreover, like Hahn, he argues that Jesus did not complete the Passover Seder on Holy Thursday, but on Good Friday, when, by accepting the wine offered to him in his dying moments, drinks the last of the four ritually prescribed cups. So,

“(B)y waiting to drink the fourth cup of the Passover until the very moment of his death, Jesus united the Last Supper to his death on the cross. By refusing to drink of the fruit of the vine until he gave up his final breath, he joined the offering of himself under the form of bread and wine to the offering of himself on Calvary… In short, by means of the Last Supper, Jesus transformed the Cross into a Passover, and by means of the Cross, he transformed the Last Supper into a sacrifice.”

Pitre’s is another book that can furnish us with a better understanding of what is going on during the Sacred Triduum.

4.

In the liturgy we do not just listen to the Word of God, but also worship God through sacred images (For more on the place of sacred images in Christian worship, read the interviews on icons and sacred art). Indeed, one of the highpoints of Holy Week is the Adoration of the Holy Cross during the Celebration of the Lord’s Passion on Good Friday.

Likely, that will not be the only moment when we pray before a cross during Holy Week, whether at Church or home. Moreover, we may choose to pray before one cross rather than another not just for convenience, but because it aids our prayer more. Maybe under other circumstances we have found another cross, very different in style, more helpful. The immense stylistic variety of crosses is a testimony to the ‘unsearchable riches of Christ’ (Ephesians 3:18) and his cross.

The variety and the unconfinable significance of the cross is still apparent within the sacred art of a single country, such as Ireland. One book which illustrates this point is Peter Harbison’s The Crucifixion in Irish Art: Fifty Selected Examples from the Ninth to the Twentieth Century.

Each entry has a page that explains the selected example and a black and white photo of it.

The crosses surveyed range from tombstones to illuminated manuscripts, from church doors to stained-glass windows. Many are not the most beautiful representations that there are. However, taken together, they reflect how deeply people have meditated on the cross over the centuries, amid varying social and cultural circumstances, and, aware of the cosmic import of Christ’s death on the cross, have sought to make it ever present in the world around us. Even if you do not find an image of the cross which you want to pray before, the iconography surveyed will make you think more deeply about the mystery and significance of the cross.

5.

Music plays a prominent role during the liturgy of Holy Week. It summons us to meditate upon certain verses of Scripture or prayers and make them our own. It expresses the emotions implicit in the text and rouses them within us. Listening to some of that music outside the liturgy can help us mediate upon the mysteries of Holy Week.

Last week’s interview surveyed two such pieces: Bach’s St. John Passion and St. Matthew Passion. The former was first performed three hundred years ago, on Good Friday.

Bach wrote his Passions for Lutheran liturgy in Leipzig. Almost two hundred years earlier, Thomas Tallis (c. 1505-1585) was composing some of the first English anthems for the Anglican liturgy.

Thomas Tallis was a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal from 1543 until his death. In that role, he served four English monarchs, from Henry VIII to Elizabeth I, right during the thick of the Reformation. Moreover, his role was not limited to that of a chorister. He would have played the organ and directed the choir too. Most importantly, he was a composer.

Tallis and his protege, William Byrd, served Anglican monarchs and wrote music for the services of the recently established Church of England. To their credit, they remained Catholics.

The clergy of the recently established Church of England had definite ideas about sacred music. As Peter Phillips has noted, they were looking for “intelligibility and clarity in the word-setting, which involved singing in English and keeping the musical style simple.” Tallis’s English anthems are an interesting example of music that he wrote to meet those demands. For Phillips, “despite the dogmatic restrictions on their musical elaboration, they maintain a high artistic standard.”

Two of Tallis’s English anthems—If ye love me and A new commandment—are perfect for Holy Week. They are settings of verses from Christ’s Farewell Discourse to the apostles on Holy

The Evening Mass of the Lord’s Supper commemorates not only Christ’s institution of the Eucharist and washing of the feet of the disciples, but also the new commandment that he has given us: to love one another as he has loved us (John 13:34-35). Tallis’s A new commandment sets these verses to music, whereas If ye love me is a setting of another, related pericope from the Farewell Discourse (John 14:15-16, 23).

Both anthems are written in binary form (ABB) and scored for two countertenors, tenor, and bass. They are tailored to the ideals of the early Anglican liturgy in several ways. First, they are written in English rather than Latin. Second, they eschew complex polyphony for simpler, more homophonic writing. The combination of both features makes the biblical text clear and understandable to the anglophone congregants.

Fittingly for music composed by a Catholic for the Anglican liturgy, If ye love me was sung during Pope Benedict XVI’s visit to Westminster Abbey for Evensong on 17 September 2010.

During Holy Week we are called to take to heart once more the commandments that Christ gave us during his Farewell Discourse. Listening to these two beautiful anthems may help us in this regard.

Above all, may the Lord lead us with his Spirit through this Holy Week to a deeper conversion and charity.