Christus resurrexit, alleluia!

Lent is just a preparation and spiritual warm-up for Easter. Now that it is Easter, it is time to get down to exercising the Christian life in full. It makes sense, therefore, to keep setting aside some time for reading about the mysteries we celebrate and how we can live them out. Here then are some books and music that might be helpful. For further suggestions, check out last year’s recommendations.

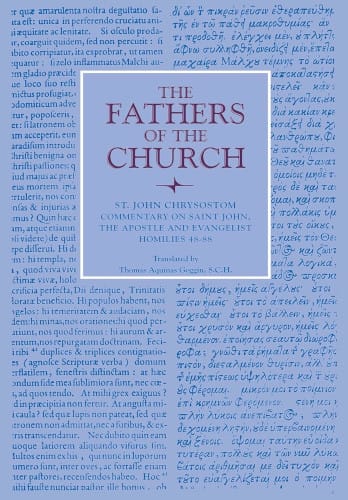

- Commentary on Saint John the Apostle and Evangelist: Homilies 48-88

by St. John Chrysostom - The Resurrection: A Biblical Study

by François-Xavier Durrwell CSsR - The Old Evangelization: How to Spread the Faith Like Jesus Did

by Eric Sammons - Understanding Early Christian Art

by Robin M. Jensen - Thomas Tallis: The Complete English Anthems

by The Tallis Scholars, directed by Peter Phillips

Five Books for Catholics may receive a commission from qualifyng purchases made using the affliate links in this post.

You can listen to the interview here.

1.

For the first recommended reading for Lent and Holy Week, we picked a Church Father. Moreover, we stuck to the same one: St. John Chrysostom. His Commentary on Saint John the Apostle and Evangelist took us through Holy Week. Now is the perfect time to read the last four homilies (85-88). They cover the fourth evangelist’s account of the Lord’s resurrection (John 20-21). In them, Chrysostom, still a priest at Antioch, unpacks the Lord’s apparition to Mary of Magdala; Peter and John’s visit to the empty tomb; the Lord’s conferral of the Spirit on the ten on Easter Sunday; his remonstrance of Thomas the following week; and his appearance to the apostles fishing at the Sea of Tiberias.

As noted last week, Chrysostom has a reputation for focussing on the moral life rather than dogmas. While he may dwell more on the former, he does not neglect to instruct his congregation on the latter too. Take Christ’s conferral of the Holy Spirit on the ten on Easter Sunday. Chrysostom discovers an opportunity to teach his congregation on the consubstantiality of the three divine persons, notwithstanding our our manner of speaking of them. The signs that the apostles perform once they receive the Spirit attest not just to Jesus but to the consubstantiality of the Trinity.

“Moreover, this took place that you might learn that the gifts and power of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit are one. What appears to be proper to the Father also belongs in reality to the Son and to the Holy Spirit.”

As to the hierarchical structure of the Church, he calls the congregant’s attention to how Christ reiterates Peter’s primacy among the apostles at the Sea of Tiberias. Chrysostom may be eager to defend that primacy as Antioch was a Petrine see. Along with Rome and Alexandria, it was one of the three ancient patriarchates. However, he clearly attributes to Peter and his successors a universal authority on doctrinal matters.

“And, if someone should say: 'How is it, then, that it was James who received the bishop's chair in Jerusalem?' I would make this reply: that Christ appointed this man, not merely to a chair, but as teacher of the world.”

As ever, Chrysostom finds surprising practical applications of the Gospel. He explains, for example, both why it was fitting for the Lord to be afforded a costly burial yet why we should avoid extravagance in our own funerals and spend the surplus on penitential works of mercy instead.

“The body that is cast out unburied is not as grievously shamed as the soul that then appears without virtue.”

Extravagant funerals may not be as big a fad now as it was back then. Given recent scandals, we are more likely to fall into another spiritual danger he mentions: disrespect negligent bishops and priests. St. John Chrysostom does not excuse such clerics. However, he carefully explains to his congregants how they put their soul at risk if, instead of attending to it, they disrespect ordained ministers.

In drawing out unsurmised implications of the risen Christ’s apparitions, St. John Chrysostom proves himself a valuable spiritual master for Eastertide.

2.

The second book for Holy Week was Fr. Philippe de la Trinité’s What is Redemption? It tries to correct the widespread but distorted view that Jesus redeemed us by satisfying the Father’s retributive, penal justice. It also makes good reading for Easter as it explains the essential role of the Lord’s Resurrection and Ascension in our redemption. In that section of the book, he states that

“For Jesus is the head of the mystical body, and the glorification of the head is not only inconceivable without that of the members but postulates, entails and realizes this.

In other words, our redemption is not an abstract notion, however rich and complex, but a living person, the Person of the Son of God made man.”

Unfortunately, this instructive section of the book is brief. Another book that appeared around the same time is a biblical study of the Resurrection as a mystery of salvation.

Fr. François-Xavier Durrwell CSsR’s The Resurrection aims to remedy a deficiency within the theology of the period. Apologists highlighted the historical credibility of the apostolic testimony on Christ’s Resurrection. However, theologians tended to treat Good Friday as the culmination of the Lord redemptive work and Easter Sunday as a sort of epilogue. However, that does not square with the apostolic preaching on the Resurrection. Easter Sunday and Good Friday are both essential moments of our redemption and inseparable from one another. but it is the former that gives meaning to the latter.

There have been developments in the scholarship since then. Nevertheless, Durwell’s accessible scholarly monograph is still valid. It provides an admirable overview of the New Testament teaching on the Resurrection as a mystery of redemption.

3.

In his various apparitions to the disciples prior to his Ascension, Jesus commissions them to evangelise. He bids Mary of Magdala to tell the apostles about his Resurrection and then charges them to make disciples of all nations. Not that they will live long enough to accomplish this task. By entrusting this mission to them, the risen Lord is entrusting it to us too. Easter, therefore, is a period to take stock of our mission to evangelise.

Perhaps the best way is to do this is to follow the Gospel at Mass during the Easter Octave and meditate on the risen Christ’s various appearances to the disciples. However, this website’s job is to suggest, in addition to that, a book that might help.

A book about evangelization in today’s world will probably help us take stock of whether we are doing our utmost to share the Good News. There are authoritative papal documents on the subject, such as St. Paul VI’s Evangelii nuntiandi and Pope Francis’s Evangelii Gaudium. There are also quite a few good practical guides to the new evangelization. These illustrate how laypersons can apply such papal documents in their specific situation. Eric Sammons, the current editor of Crisis Magazine, has written one such book for Catholic Answers. It offers plenty of practical advice and relatable cases. Provocatively, however, it advocates an old evangelization.

Sammons does not object to John Paul II’s call for a new evangelization. Rather, he objects to construing it as a break with the missionary endeavours and methods of the past. He also questions the validity of the new methods that have gained currency.

“What I’ve found is that most Catholics model their evangelization (if they do it at all) on one of two examples: successful corporate marketing or Protestant megachurches. Instead of looking to Jesus, we take Steve Jobs and Joel Osteen as our models. The resulting approaches tend to downplay Catholic doctrine, the Mass, and the “hard” teachings of the Faith, and they aim less at attracting disciples than at gaining cultural acceptance. Ignored is the Church’s rich patrimony of evangelizing models and methods, reaching back to Jesus himself.”

Sammons, therefore, looks to how Jesus evangelises in the Gospels. He also examines cases from his own life and surroundings in the light of Christ’s example. In the process, he argues that more accommodationist approaches to evangelization, though well-intention, are misguided and, well, not very evangelical.

To bring the lessons home, each chapter concludes with some suggestions on how to put them into practice and questions for further reflection, as well as an example from the life of a saint.

This book on evangelization is helpful because it is straightforward and takes a back-to-basics approach.

4.

The writings of the apostles and the Church Fathers are not the only window into the early Church. So is the art of the early Christians.

We might acknowledge this but dismiss it for being of little importance. That would be a mistake. We are animals, not angels. The senses play an essential role in our life, starting with the sensible objects, such as bread and water, by which God communicates grace to us in the sacraments. Indeed, Christ’s Resurrection attests to the dignity and importance of our corporeity.

Sacred art is essential on account of corporeity. We need to see images that remind us of God, the saints, and the central episodes of the history of salvation. By depicting the beauty of God, his saints, and his works, sacred art draws us to contemplate them.

Of course, sacred art is unintelligible without the Word of God. At the same time, it is also an interpretation of Scripture.

In this regard, early Christian art is particularly instructive for Easter. Christ’s Resurrection and our participation in it through baptism are its central themes. Besides being the initial stage of sacred art, it evinces how keenly aware early Christians were the centrality of his Resurrection. Moreover, it often offers an important commentary on the early liturgy and the writings of the Church Fathers.

As Prof. Robin M. Jensen explained in an interview on early Christian art,

“Most of what we have from the earliest period comes from the Rome area.

We have a few examples from the East and the Western part of the Roman Empire, but our early Christian material is concentrated in Rome and its environs. There are catacomb paintings. There are the carvings on early Christian monumental sarcophagi or burial boxes (made out of marble but sometimes limestone). That is a wonderful collection that we have in Rome and some other places, such as Naples and Arles,

The earliest iconography—I say iconography rather than art—starts with simple symbols: the simplest forms of birds, praying figures, shepherds, and sheep.

However, early on, what distinguishes Christian art and makes it more identifiable are its unique biblical scenes...

What we do not see clearly is the crucifixion. There are some references to the Passion story. Sometimes we see Jesus before Pilate or Simon of Cyrene carrying the cross, but, with some rare exceptions, we do not have an image of the crucifixion before the fifth century.”

Rather, the symbols and biblical stories used in early Christian art are connected with baptism, the Eucharist, and the Resurrection.

An excellent survey of early Christian art is Jensen’s Understanding Early Christian Art.

Besides looking at early direct depictions of Christ’s Resurrection and Ascension, it explains the symbols and biblical stories that feature most prominently in the art of the early Christians. With the grapevine, they allude to the Eucharist. They express their faith and hope in eternal life and the Resurrection with symbols such as the peacock and phoenix, or certain episodes from the Old Testament, such as Jonah or the three young men in the fiery furnace. Many of the biblical stories that matter most to them point to Baptism: crossing of the Red Sea, Moses’s striking of the rock from which water flowed, Jonah, and Christ’s encounter at the well with the Samaritan woman.

5.

Music is just as an important part of the liturgy as art. So, the final recommended book for Holy Week was not a book at all, but a music recording. Listening to some sacred music outside a service can still help us mediate upon the mysteries of the liturgical season and stir our hearts to them.

The proposed disc was a recording of Thomas Tallis’s English Anthems.

As explained last week, Tallis composed sacred music for the first Anglican monarchs. Moreover, his English anthems are tailored to the standards for sacred music set by early Anglican liturgists: compositions in the vernacular whose relatively simple style makes it easier for the congregants to follow the biblical text.

The Tallis Scholars’ recording of his English anthems also includes a composition for Easter: Christ Rising Again, a setting of Christus resurgens, a motet for Easter Sunday that is drawn from Romans 6:9-11 and 1Corinthians 15:20-22. This may be a late composition by Tallis. It may even be by his protégé and fellow Catholic, William Byrd.

It is written for five voices (MATTB), for Matins on Easter Sunday, and is divided into two parts, the first a setting of Romans 6:9-11, the second of 1Corinthians 15:20-22. The music develops with one voice imitating another and it ends with a series of ascending Easter Alleluias. This anthem is both a proclamation of the Easter message and a prayer of praise.

During this Easter, may we who have been raised with Christ, continue to “seek the things that are above” and ponder “the unsearchable riches of Christ.”