Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750), one the greatest Western composers, left behind vast and equally impressive bodies of instrumental and vocal music. The vast majority of his vocal compositions consists of sacred music written for Lutheran services. Most of it was written during his stints as Konzertmeister at Weimar (1714-1717) and director of church music, or Thomaskantor, in Leipzig (1723-1750).

Here is the second part of an interview with Daniel R. Melamed. In the first part he discussed Bach’s Passions. In the second part, he discusses some resources on Bach's other sacred music.

Daniel R. Melamed is professor of music in musicology at the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music. His research interests focus on J. S. Bach, Mozart-era opera, and music of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. He is president of the American Bach Society and director of the Bloomington Bach Cantata Project. He has authored Listening to Bach: The Mass in B Minor and the Christmas Oratorio, Hearing Bach’s Passions, and J. S. Bach and the German Motet, and co-authored (with Michael Marissen) An Introduction to Bach Studies. He is editor of Bach Studies 2 and Bach Perspectives 8: J. S. Bach and the Oratorio.

- Listening to Bach: The Mass in B Minor and the Christmas Oratorio

by Daniel R. Melamed - Bach

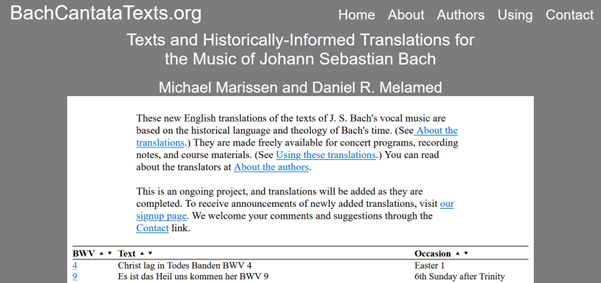

by David Schulenberg - Texts and Historically-Informed Translations for the Music of Johann Sebastian Bach

by Michael Marissen and Daniel R. Melamed - Bloomington Bach Cantata Project

directed by Daniel R. Melamed

You have also recommended some other books and resources on Bach’s sacred music. Before touching upon them, could you explain what drew you to dedicate so much time and interest to Bach.

It started with the pure musical appeal of the repertory, especially the vocal music, which I was hooked on when I sang it as a young chorus member.

Then, I discovered the world of Bach scholarship. It is full of puzzles and problems. There is an enormous amount of historical information to be sorted out. It gave me a surprisingly good view of Bach as a practical working musician.

This combination of things made me want to know his music more so that I could listen to a work, consider it, and understand it better from many points of view. The more I got interested in Bach, especially his vocal-instrumental music, from that point of view, the more I began to appreciate Bach’s accomplishments, his power as a musical thinker, and the degree of skill of craft that he brought to this music.

I also became interested in the intersection between all this technical evidence, on the one hand, with the way these pieces generate meaning in a given time and are important to people. Ever since, I have spent a lot of time thinking about the relationship between those things. What has really kept me engaged is the question of how a performance of this piece is connected to the way in which it is understood. So, I was drawn in as a singer and then as a technical scholar. I would like to think that I have broadened my thinking about Bach’s music since then.

"We should think about how singers and instrumentalists back then conceived what they were doing as opposed to how contemporary ones conceive what they are doing. "

1.

The first of the additional books you have recommended is a companion volume to your Hearing Bach’s Passions. In Listening to Bach you examine two of his other great works of sacred music: the Mass in B Minor and the Christmas Oratorio. Each of these is a parody. In each, Bach sets the text to music he had already composed and used in other works. However, you argue that focussing on the parodic character of these works might not be helpful and that we should try to listen to them as Bach’s original audience would have. Could you tell us a bit more about this book?

Yes. Hearing Bach’s Passions uses these works and Bach’s Passion repertory as a starting point for examining a whole series of problems about what it means to confront an old work of music today.

We need to think about the way it is performed now as opposed to how it was performed then. We should think about how singers and instrumentalists back then conceived what they were doing as opposed to how contemporary ones conceive what they are doing. What does it mean to identify a fixed text of a great work of art such as the St. John Passion? As it turns out, there is no such thing. As you and I were discussing earlier, Bach would not necessarily have understood the idea that a piece in his working repertory was fixed. These are some of the problems inherent in a confrontation with old music.

In Listening to Bach: The Mass in B Minor in the Christmas Oratorio, I wanted to go from thinking about the problem of confronting old music to the question of how we listen to that music: to its notes and words. Much of the book is about the demonstrable fact that Bach adapted much of these two works from pieces that he had composed earlier for other purposes. He assembled and reworked these pieces, sometimes in a process whose technical name is parody, and sometimes by other processes. However, just as In Hearing Bach’s Passions the Passions are the vehicle for talking about the problems of confronting old music, in Listening to Bach I take parody as a starting point for considering what it means to listen carefully to this music. How would people have listened to it in Bach’s time? What can you learn as a modern listener about the way this music is put together? When you circle back to the problem of what it means that the same notes could serve different purposes, you come to bigger questions about how early eighteenth-century vocal-instrumental music worked.

"The segments of the piece that we call the Mass in B Minor were not only usable and conceivable as Lutheran music, but were conceived as such."

The Mass in B Minor, if I am not mistaken, is one of Bach’s last works. But why did Bach, a Lutheran, write a setting of the Catholic Mass?

That is a question that has been argued and debated, and the pendulum has swung back and forth on this. The latest view is going to be represented in a forthcoming essay by my friend and colleague Michael Marissen, whose Lutheranism, Anti-Judaism, and Bach’s St. John Passion we just discussed. He argues that each part of the Mass in B Minor, a title that Bach never applied to that collection of movements, was in theory usable in Lutheran liturgy and that, in many important respects. Bach’s musical treatment represents distinctly Lutheran theological perspectives on the Mass Ordinary. You tend to agree with your friends, so I like these points and believe that Michael is right about this. The segments of the piece that we call the Mass in B Minor were not only usable and conceivable as Lutheran music, but were conceived as such.

On the other hand, Bach assembled and bound all the movements of the Mass Ordinary into a single volume. Famously, his second oldest son, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, called it “the great catholic Mass.” It is not clear whether he meant this in a technical or a confessional sense. Although we can demonstrate satisfactorily that this music was usable for Lutheran worship, we cannot simply dismiss the fact that this collection of the five movements of the ordinary has the shape of a Catholic Mass. There is much more to be said about this. Every generation will have to come to terms with it on its own.

2.

Bach came from a family of musicians, worked his whole life as a musician, and successfully trained some of his sons in the family trade. So, some knowledge of his life and the conditions under which he works is helpful, if not essential, for understanding his works. What makes David Schulenberg’s biography a good one?

This is the most recent comprehensive biography of Bach. Schulenburg brings to it an unsurpassed familiarity with the documents, facts, and biographical research on Bach. He also brings a comprehensive knowledge of the repertory. He has done an outstanding job of writing a compelling narrative of a musician’s life. It meets the goal of almost every musical biography. It finds ways to talk about the music and its relation to Bach’s life without falling into the Romantic traps of imagining that this music was the expressive product of his feelings at each stage of his life or of every position he held. Schulenburg does a terrific job of showing the historical, musical, and working context of so much of Bach’s repertory. Between its expertise, readability, and the way it weaves together Bach’s life with the context of his musical works, it is absolutely to be recommended.

3.

With Michael Marissen you run a website with texts and historically-informed translations for Bach’s music (bachcantatatexts.org). It lists the translations according to the liturgical occasion for which they were composed. How can people use this site and its translations?

Michael and I started bachcantatatexts.org during the pandemic to deal with our mutual frustration over the many translations of Bach’s vocal works out there. Very few of these translations are done with any expertise in historical German or in early eighteenth-century Lutheran language. Hence, most of the translations out there do not render the actual meaning of the texts satisfactorily. We ask what an eighteenth-century listener would have heard. We bring a knowledge of historical German and especially a knowledge—and this is this Marissen’s strength—of Lutheran writings, Scripture, and theology. This brings out the topics and themes that are being addressed in the text.

It turns out that people have been mostly right about most of what is in the text. Nevertheless, in every cantata we discover crucial moments in which the language has been misunderstood. If you understand the historical usage and, above all, the Scriptural and theological references, you have a much better idea of what the poet or librettist was after and, presumably, what a theologically informed member of the congregation would have heard.

We hope that people will turn to these translations. We have tried to make them self-standing. However, they also have extensive annotations. They explain certain choices we made, the scriptural references and their import, the historical meanings of words.

We have set it up so that they can be read quite well on the phone. There is even a dark mode for the concert hall. So, you can even follow the translation during a performance without disturbing your neighbour.

We are coming up on our hundredth text. We have just done four different versions of the John Passion. It shall take us a few years to translate everything else, but we are continuing the project.

Just as Gustav Leonhardt or John Eliot Gardiner have recorded all the cantatas, you have translated them all.

I would love to have recorded them all. Our task is slightly little different and can be undertaken by a duo. Recording them all took enormous teams of expert performers who came together to make music year after year after year. Although I have some differences with the approaches taken in many recordings of Bach’s cantatas, I am astonished by the effort it must have taken to rehearse, perform, and record all of them.

"We are determined to model our performances of Bach cantatas on his own. That turns out to be an ear-opening experience for performers and listeners alike."

4.

And finally, could you tell us a bit about another of your projects: the Bloomington, Bach Cantata Project?

The Bloomington Bach Cantata Project is in its fourteenth season. We present performances of J.S. Bach’s cantatas in free public concerts, six times a year, in Bloomington, Indiana. The performers are specialists in eighteenth-century singing and instrumental playing. We pay very close attention to what we know about the size of the forces that Bach used. We pay close attention to the musical texts and to the multiple versions in which pieces have come down to us. In no sense, are we chasing after recreations of Bach’s performances. However, we are determined to model our performances of Bach cantatas on his own. That turns out to be an ear-opening experience for performers and listeners alike.

The concerts have a format that, to my knowledge, is not followed anywhere else. First, the audience hears a performance of the cantata. Then, there is a talk on it. Typically, I give it. In it, I talk about problems of music, text, theology, and listening: many of the things that you and I have been talking about. Finally, the audience has a chance to hear the performance a second time. All this can be fitted into the concert because the cantatas are fairly short. Consistently, people say that they have heard new and different things.

We are in our fourteenth season. We can be found on YouTube and Facebook. For those who cannot come to Bloomington, we post good video recordings of every concert. It has been ear-opening for me and a delight to train a couple of generations of mostly young musicians and perform in this very challenging way. Musically, the results have been terrific. Every time I get to participate is a thrill.